This is the third and final part of the History of Pointing Dogs series. Here are links to

Part 1 and

Part 2.

|

Field Trial Judges, France 1913

|

Field trials were first run on the continent in the 1880s. Initially, British breeds, continental breeds and even half-breed mixes would sometimes run in the same stakes. Unfortunately, the results were almost always the same. Pointers and Setters, bred for generations to seek the horizon at a gallop, simply ran circles around the completely out-classed continental dogs that were bred to hunt at a trot, more or less within gun range.

Clearly, unless some adjustments were made to the rules and format, continental breeds were in danger of either turning into just another version of the Pointer or setter, or of disappearing altogether. So it was eventually agreed that British and Continental dogs should run in separate stakes. In many countries, that division is still in place today.

But even as the first trials were being run in the 1880s, questions about their effectiveness as a selection tool were being raised. Hunters in some areas, Germany in particular, questioned the very narrow focus of the events. So they began to organize forest trials, water trials and non-competitive tests designed to evaluate every aspect of what were then called “practical hunting dogs”.

They eventually decided to follow the principles of livestock breeding instead of the horseracing model upon which field trials were based. After all, they were not looking for a one-in-a-million winner to use in highly inbred lines. Their goal was to establish and maintain a strong population of dogs that had all been tested and proven in as many ways as possible. But, in the early days, progress came mainly through trial and error. William Heinrich, a GWP breeder in Germany who shares my interest in the hunting dog history provided me with the following observations about the period:

Despite the fact that many of the men involved in these efforts were highly educated, they had little practical and theoretic knowledge that they could apply to the field of dog breeding. This presented breeders with a number of new challenges. One of them was how to combine different types of dogs into a single breed while retaining the various abilities of each. Today it seems hard to believe that those breeders did not have a very good understanding of breeding principles. After all, Mendel’s experiments, carried out in the 1850s, should have shed tremendous light on the mechanisms of heredity. Unfortunately the general public did not even hear about Mendel’s work until well after the turn of the 20th century.

When the German versatiles were created, breeders did not even know that there is a genotype behind the phenotype! Reading the old publications, you get a sense of their frustration and despair. Things happened that they did not understand. We can now see that they discovered everything by countless experiments. Our breeds were developed by trial and error. This leaves a wide field for interpretation. That’s why history is so fascinating and why historians never agree.

|

| Hegewald |

The system that eventually proved the most effective was one that combined comprehensive testing with strict breeding controls. Several men are credited with coming up with the idea. The most famous is

Sigismund Freiherr (Baron) von Zedlitz und Neukirch. Writing under the pen name Hegewald, his untiring promotion of the versatile hunting dog concept is what eventually led to the creation of all the German pointing breeds. He is also credited with helping establish the Deutches Gebrauchshunde-Stammbuch (German versatile dog stud book). But his single most important achievement was the successful battle he fought for the establishment of a performance-based testing and breeding system.

|

| Oberlander |

Another leading figure was

Carl Rehfus who wrote under the pen name, Oberländer. Like Hegewald, Oberländer was a nationalist. Highly critical of the British pointing breeds and the “Anglomania” in certain circles of German society of the time, he insisted that there was no need to use English blood in the development of the German versatile breeds. He was also very much against the idea of dog shows and wrote scathing articles about the direction that Germany’s dog establishment was taking.

Eduard Korthals and his patron,

Prince Albrecht of Solms-Braunfels, also worked hard to establish the new system. But Korthals was an internationalist who tried, but ultimately failed, to establish a pan-European versatile dog movement.

By the 1930s, the majority of breeders in Germany were convinced that, for their purposes, a non-competitive testing and breeding system was superior to the field trial and dog show system used elsewhere. But it wasn’t until the 1960s that hunters beyond Germany, and its neighbors to the east, started to understand why.

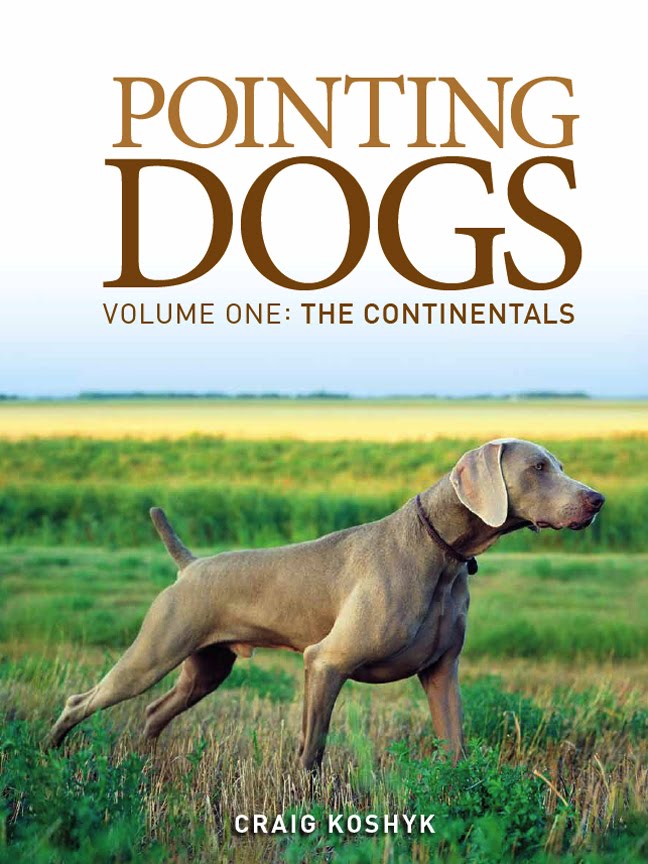

Pointers and Setters had been in North America since colonial times, and it is likely that a few individual pointing dogs from the continent made their way across the Atlantic with the waves of immigrants in the late 1800s. But serious efforts to establish viable populations of Continental breeds in North America did not really get under way until after the First World War when small but increasing numbers of GSPs, Weimaraners, Brittanies and Griffons began to appear in the US and Canada. But when war again broke out in 1939, everything came to a grinding halt.

After the Second World War, vast areas of Europe lay in ruins, millions of its citizens had lost their lives, and many of the Continental pointing dog breeds were on the verge of collapse. At first, recovery was slow and difficult. Breed clubs had fallen apart, studbooks had been destroyed, and thousands of breeders and their dogs had perished. But almost as soon as the shooting stopped, dedicated men and women across the continent began the arduous task of rebuilding, and in some cases completely recreating, their breeds.

And it wasn’t long before many of the tens of thousands of allied service personnel stationed in Europe found out about the local gundog breeds. By the 1950s they were buying as many as they could get their hands on and shipping them home to booming markets in North America and the UK. In the 1960s, as a growing middle class with more leisure time and disposable income than ever before grew across the western world, interest in the outdoor sports, field trials and dog shows exploded.

And it wasn’t long before many of the tens of thousands of allied service personnel stationed in Europe found out about the local gundog breeds. By the 1950s they were buying as many as they could get their hands on and shipping them home to booming markets in North America and the UK. In the 1960s, as a growing middle class with more leisure time and disposable income than ever before grew across the western world, interest in the outdoor sports, field trials and dog shows exploded.

As a result of all the interest—and undoubtedly the lure of quick money—dog populations skyrocketed. In less than a decade, breeds that had been completely unknown before the war were now numbering in the tens of thousands. The first attempt to organize non-competitive hunt tests was made in Canada, in 1963, by the All Purpose gun Dog Club of Ontario. The club was mainly made up of field trial enthusiasts who wanted to add a water-work component based on retriever trials to their events. They began by adding some German test regulations to North American field trials rules, but for various reasons the club did not last long. It was disbanded in 1965.

|

| NAVHDA Judges |

Undeterred, former club member

Bodo Winterhelt, a German immigrant living in Canada, began to work on a new format. In May of 1969 he and other gundog enthusiasts met to form a new club. Their goal was to create a new system based on elements of German tests that would be modified to better suit North American hunting traditions. One of the first orders of business at the meeting was to choose a name for the club. After much debate, the members chose north American Versatile Hunting Dog Association, or

NAVHDA. They also agreed to focus on recruiting owners of hunting dogs to the new club instead of trying to convince field trial enthusiasts to adopt a new format. John Kegel, at whose home the first meeting was held, wrote that at the end of the first meeting no one had any idea of just how big the club would eventually grow.

Once my liquor supply was exhausted, everyone left not knowing that they had started a new movement that soon would expand to the United States and make history in the hunting dog world.

The first NAVHDA tests were held in October of 1969 and May of 1970. Growth for the new club was slow at first. Field trials, which had been run in North America for nearly a century, dominated the sporting dog scene, and it was very difficult to convince people that there were others ways to evaluate the hunting abilities of gundogs. Even well-known dog trainer and writer, David Michael Duffey, could not quite get his head around the idea of non-competitive testing. Writing in the January, 1973 issue of Outdoor Life magazine he described NAVHDA testing as ... a form of field trialing that’s relatively new and strange to North American sportsmen and a somewhat alien concept... not likely to spread like a prairie fire in the next few years.

Duffey was correct in predicting a slow start to the new club, but things picked up steam in the late 70s and 80s and by the 1990s, it was growing rapidly. Today, NAVHDA has a membership of over 5,000 sportsmen and women. Its 65 chapters in the US, and nine in Canada, run a total of over 300 tests each year in which over 2,000 dogs are evaluated. What began as a small club with only a handful of early supporters is now a dominant force on the versatile pointing dog scene in North America.

|

| JGHV Test |

Meanwhile, in Europe, the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989 led to the reunification of breeds that had been separated 50 years earlier. Then, in the mid-1990s, the Internet came along. It was the most significant development on the gundog scene since the invention of gunpowder. Today, there is hardly a breed club in the world that does not have a web presence. For many individual breeders having a website is just as important as having a heat lamp over the whelping box.

Almost overnight, the Internet stimulated renewed interest in many of the established breeds and breathed new life into breeds that had been struggling for years. These leading-edge technologies have also contributed to the transformation of the gundog scene. We now produce puppies via artificial insemination and test their DNA to screen for health concerns. We vaccinate our dogs and feed them store-bought food. We transport them in airliners and four-wheel drive trucks and we keep track of them in the field with the help of satellites floating in the sky above.

But there are some threats looming on the horizon. The most significant among them is the alarming decline of outdoor sports in much of the western world. In many regions, increasingly restrictive hunting laws are being passed and anti-hunting movements are gaining ground. Access to hunting areas is harder to come by and even field trial clubs and testing organizations are having a tough time finding suitable grounds for their events. And sadly, as older hunters pass on and fewer youngsters take their place in the hunting field, the hunting culture for which our pointing dogs were designed may one day fade away.

Yet, in spite of it all, some things will never change. We will always love our pointing dogs, and through them, forever seek a closer connection to the natural world.